DRUM Card Opportunity: Using complete sentences and proper spelling/grammar, tell me what you learned by perusing (browsing, reading, looking through) this post. Use at least 3-5 sentences. (Trust me, with the amount of stuff in here, 3-5 sentences will be a breeze!)

Pulaski's spring break was a couple weeks ago, and some of us used this time to venture to warm places. I spent part of my break in Arizona. The temperatures were lovely, the fresh air smelled like plants, the sunshine was warm...

Oh, and the landscape wasn't too bad to look at.

You get the picture.

Here comes some travel advice from Ms. G: If you're ever in Phoenix, Arizona, there is one place you HAVE to visit. It's called the

Musical Instrument Museum, and it's amazing. I went there with a couple of my music teacher friends, and we explored a vast wealth of musical and cultural resources from around the world.

Before I start telling you about some of the things I saw (and showing you the pictures I took), I want to toss out a vocabulary word to you: culture. Most simply put, culture is people's way of doing things. It varies between groups of people, even between groups of people in the same area. For example, Pulaski's culture might be slightly different than Green Bay's culture, which is different than Milwaukee's culture. We could also look at larger groups of people. For example, Wisconsin's culture is different than Florida's culture, the USA's culture is different than France's culture. We can't judge other cultures as "right" or "wrong" - they might just be different than ours. (It's really neat to find the similarities too!) This is where learning happens: when we open our minds to new possibilities and new ways of life, not necessarily to imitate them, but to accept them for what they are.

Okay, now that we've gotten the introduction out of the way...let's explore a little bit of what I saw at the MIM! By the way, I linked countries and states to pictures of maps so you can get a better idea of where they're located.

There was a guitar exhibit downstairs, and there were some interesting variations on guitars. For example, this is a harp guitar that was manufactured in

Michigan:

Here's a harp guitar from

Germany:

There was also a small variety of instruments past the guitar exhibit. This little guy (on the left) is a miniature violin that was made in

Germany around the year 1900. The sign next to it says, "Makers or apprentices would often make miniature instruments to showcase their skills."

Speaking of things in different sizes, these are four differently sized

Russian balalaikas (three-stringed triangular-bodied instruments):

This next instrument was large! The sign next to it says:

Tabo (goblet drum)

Tugaya, Lanao del Sur,

Philippines, 1959-1979

Karim Saud Basudan, maker

Here come some more interesting instruments. This is what a sign said underneath the following exhibit:

"Although no one knows for sure, humans probably used their voices and their own bodies as the first ways to create musical sounds.

"Since then, just about every material imaginable, both natural and manufactured, has been used in some way or another to create musical instruments. Some unusual animals materials shown here include the ram's horn of the shofar and the lower jawbone of a horse used as a rattle. Sometimes, makers choose unexpected materials—for instance, porcelain for a violin and glass for a trumpet. Besides acoustic properties, the choice of materials used to musical instruments can depend on factors such as aesthetics, tradition, spiritual beliefs, cost and rarity, and local availability."

Pictured below is an ornamental violin made of porcelain. It's from

Italy and was made in the 1800s.

Below the violin is a glass trumpet. We would call this a natural trumpet because it has no valves. It was made in

Belgium (a country in Europe) in 1979.

The MIM had hundreds of instruments I had never seen before. One of the unique ones was the Strohviol, pictured below (top half of the photo). It's a combination of a horn and a violin. This particular example is from Paris,

France, in the first half of the 1900s. This type of instrument was invented by a British electrical engineer named Augustus Stroh for the purpose of sound amplification in the early days of sound recording. Therefore, the horn doesn't act as a brass instrument, but as a resonator (similar to the resonators on marimbas and xylophones, right, 4th and 5th graders?).

Below the Strohviol is a tenor horn in B-flat. This example is from the

Czech Republic in the mid-1800s. It was made by a man named Augustin Heinrich Rott.

There are all sorts of neat string instruments out there beyond the well-known ones (violin, viola, cello, double bass, guitar, harp, piano). Here are a couple exotic yet domestic (unusual yet from this country) ones: A concert zither made in

Missouri in the early 1908-1909 is on the left, and an Appalachian dulcimer made in

Kentucky in 1933 is on the right.

Now for a drum that was made in

New York - this

udu (vessel drum) was modeled after a traditional Nigerian drum, the

abang mbre. (

Nigeria is a country in Africa, and in Nigeria, the word "udu" means pot. So yes, this literally is a pot, or a vessel, and it also functions as a drum.) The traditional drums are too fragile to move, so that's why this one was created in the US.

Another display sign:

"Musical instruments can be a means of visual as well as sonic expression.

"Makers often strive to make their instruments beautiful, but

it is important to remember that ideas of what constitutes beauty vary greatly with time and place. Craftsmanship can be found not only in elaborate decoration such as the serpent-head bell of the

basson russe or the intricate inlay on the

darbuka, but also in the complex multistringed design of the

hardingfele or the simplicity of the ocarina. While outward aesthetics are the most easily apparent, the beauty of a musical instrument's workmanship is not only found in the way it looks and sounds, but in the way it plays."

Before we check out some more instruments, let's hit an important vocabulary word from the preceding paragraph:

aesthetics. Aesthetics is basically a theory of what is beautiful. The highlighted portion of the display sign (my highlight, not theirs) is very important to remember when we're talking about any kind of beauty. We all have different ideas of what is beautiful, and beauty doesn't always have to be about what

looks beautiful. Some things sound beautiful, or the concept behind them is beautiful. Sure, when things are nice to look at, it doesn't hurt...but outward appearances can be deceiving.

The neat-looking instrument on the left is a water-spirit flute from

Papua New Guinea. Not only is it functional as an instrument, but it's also a work of art! The small blue and white piece below it is a

German ocarina from around the year 1900. To the right is a mandolin from St. Louis,

Missouri, from around 1920.

Here's the serpent-headed

basson russe (bass horn) mentioned in the display sign. Neither a bassoon nor Russian, the "Russian bassoon" (as translated) was likely developed in

France. This example is from the first half of the 1800s. It looks fierce!

After we explored a bit downstairs, we went upstairs. This is where the magic starts to happen. The MIM is laid out by continent (North America, South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, Australia, Antarctica), with each country represented within its respective continent. We didn't visit every continent in our hours at the MIM...so I guess I'll have to go back and visit again!

Anyway, the first continent we visited was...

AFRICA

The first exhibit we checked out in Africa was for thumb pianos. I'm leaving the picture of the display sign below so that you can check out the pictures, but here's the information from it (so you don't have to strain your eyes too much!).

"For centuries, the thumb piano has been a preferred instrument of storytellers, historians, and ritual experts throughout Africa.

"Sanza, chisanji, likembe, kalimba, and mbira are among many culture-specific or regional names used to refer to thumb pianos (lamellaphones). Thumb pianos are used to accompany commemorative songs honoring chiefs and ancestors. They may also be played to interact with the spirit world or for entertainment.

"To make a thumb piano, a specialist carves a wooden soundboard and finishes it with a small adze, knives, and an iron poker used to drill holes into it. Keys/tongues (lamellae) and the pressure bars and bridges are nowadays manufactured from recycled metals. The keys are cut-to-shape in different tuning-related sizes. The handheld instrument is played by depressing or plucking the lamellae fixed to the soundboard."

Thumb pianos look pretty cool! They're made in a similar fashion, but there are different ways they can be put together, hence the different examples you see below.

From the thumb pianos, we moved on to:

"Early 16th-century Portuguese explorers and missionaries documented the great timbila (xylophones) orchestras played by the Chopi.

"The Portuguese were fascinated by the fresh rubber wound around the wooden beaters, years before Europeans were aware of rubber's uses.

"The

mbila (singular of

timbila) survives today thanks to its greatest 20th-century musician, Venancio Mbande. After large gatherings were banned by the Portuguese, Mbande trained

timbila orchestras in exile in the Johannesburg mines for almost fifty years. Recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO, the Chopi

mbila is pictured on Mozambique's currency.

"Other peoples in Mozambique include the Nyungwe, known for their

nyanga panpipes; the Shona, famous for their

mbira lamellaphones (thumb pianos); the Makonde and Makua, who play xylophones, lamellaphones, and drums; and the Shangaan, who play the gourd bow to accompany singing."

Check out the

mbila (xylophone from Mozambique) kind of hiding behind this sign.

These gumboots from South Africa can be used as an instrument. The sign next to them says, "Prohibited from speaking, miners developed their own mode of communication by slapping their rubber boots. 'Playing the boots' with energetic steps and gestures became a vibrant musical form."

On the left are ankle rattles made of fruit shells and leather, and on the right is a rattle made of wood, seedpods, and raffia fibers.

On the left is a double-headed conical drum (two drum heads, shaped like a cone) from the DRC in the early 1900s. It is made of wood and skin. The small sphere on the right is a vumi (vessel flute) made of a fruit shell.

This is a footed drum made of wood and skin. It's from the early 1900s, made by the Kongo people in the Lower Congo Region. Can you tell what it's carved to look like? Like some of the other instruments (like the rattle from Uganda two pictures up), it was created to be functional as an instrument and as a piece of art.

This is another visually appealing instrument. It's a

kwebol (goblet drum) from the Kuba people. It's made of wood, copper, cowry shells, beads, antelope skin, and nut shells. Imagine how long it would take to create the patterns on this instrument!

Check out the variety of whistles below! They are all made of wood, fiber, or ivory. The instruments in this picture are from a variety of DRC ethnic groups: the Yaka, Chokwe, Pende, Kanyoka, and Songye peoples are represented.

Here is the information from the next display sign, with the picture of it included below for the photos it contains.

"In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, instruments such as drums, slit drums, double bells, and whistles have practical and spiritual meaning.

"Some of these instruments are owned by chiefs and used to communicate important messages to their people through encoded sounds. Elaborately carved whistles are particularly significant because the instrument's 'enticing sound' is associated with the voices of ancestral or protective spirits and serves as a way to speak to spiritual forces.

"Some whistles are played in combination with healing practices, while others are used to attract animals during hunts or to lure enemies into traps. Admired as works of art, whistles are also considered status symbols. Celebrated individuals, such as chiefs, prominent hunters, and diviners, wear or hold the instruments to demonstrate their rank."

"The lyre, played throughout Sudan, migrated from the Middle East through Saharan Africa and into sub-Saharan Africa.

"Northern kisir lyres are often played for dance, while those in the south, such as the tom lyre, accompany bardic poetry and praise songs.

"The largest country in Africa, Sudan is divided north and south by the Sahara Desert and east and west by the Nile River. The Islamic Arabs of the north use drums such as the nuba to accompany religious music. Apart from the lyre, the eastern Sudanese Arabs play one-stringed umkiki fiddle, the kurbi harp, and a variety of drums. Groups in southern Sudan are known for ensembles of one-pitched wind instruments such as the now-rare Bongo mandjndji and Dinka side-blown trumpets on display."

Notice how decorative these tom lyres are - they have numerous beads and shells on them.

Fourth and fifth graders, do you remember the double reed instruments we talked about in class? We discussed the oboe, English horn, bassoon, and contrabassoon. Did you know that there are many different kinds of double reed instruments around the world? As I came across more and more of them from different countries throughout the museum, I thought of you guys! I tried to get as many pictures as I could for comparison. It's interesting how something similar in concept to the double reed instruments of our culture was created with a different-looking outcome. It would be awesome to compare their sounds!

Here are two different examples of a

mizmar (double-reed pipe). They're made of wood and metal. Notice that there aren't any keys (like an oboe has), only finger holes (like a recorder has).

How about these babies? Starting from the bottom left and working our way around clockwise, we've got

kaşik (spoons, often used as clappers while dancing),

mey (double-reed pipe), the double white tubes are a

zambur (double single-reed pipe made of animal bone and reed; this example was made in 1972), the

sipsi (a single-reed pipe), the instrument with the dangling stuff on it is a

cura zurna (a double-reed pipe made of wood, metal, beads, and bulrush), and the three instruments on the end are different types of flutes.

After exploring African instruments (I didn't even take pictures of everything I saw, if that gives you any idea of how extensive this museum's collection is), we moved on to our next continent...

ASIA

Hey look, another double reed instrument! This is a

surnay, and this particular example is made of apricot woods, cow horn, metal, and reed. Click on the link to hear what it sounds like.

Guess what - more double reed instruments! These are examples of the

nagaswaram. Below them is the

gottuvadhyam, which is a type of fretless lute. (Remember, frets are those ridges on the neck of some string instruments, like guitars, that help the player find where the different pitches are located on each string.)

The thin instrument up top is called a

di, and it's a single-reed pipe. The two instruments below it on either side are examples of the

lusheng, which is a mouth organ. The one on the left is made of metal, bamboo, and textile, while the one on the right is made of bamboo and hardwood.

This interesting-looking instrument is called an

ever büree. It's a single-reed pipe made of brass, wood, cow bone, and cane. Historically, it was once made from animal horn and had no keys.

This mouth organ from northern China is called a

fangsheng, and it's made of rosewood (which is the type of wood marimba bars are made of) and bamboo.

Before reading this next display, think about how we divide our instruments into categories. (The easiest way to divide them is by how you play them - percussion, strings, woodwinds, and brass. The ethnomusicology way of doing this still divides them by how they produce sound, but the

categories—chordophones, aerophones, membranophones, idiophones, and electrophones—cover instruments that don't necessarily fit into the Western orchestral classification of instruments.)

"In ancient China, musical instruments were divided into 'eight sounds' (bayin) based on the materials used in their construction: metal (jin), stone (shi), silk (si), bamboo (zhu), gourd (pao), clay (tao), leather (ge), and wood (mu).

"Today, imperial court and ritual musical instruments associated with this early classification system are reconstructed for use in ensembles that perform in museums and historical buildings. The set of 12 bronze

metal bells

(bianzhong),

stone chimes

(bianqing),

leather-headed drum

(jiangu), and

wood scraper

(yu) were once used in Confucian rituals. The

xun clay vessel flute,

sheng gourd mouth organ, and

paixiao bamboo raft flute were in use at least 2,000 years ago. The

qin, a zither with

silk strings, is a solo instrument long identified with Chinese scholars."

Yikes, I didn't realize how few pictures I took in the Asian exhibits!

EUROPE

The following picture has the country of

Liechtenstein labeled in it, but the instruments in this shot are not from that tiny country. The

geige (violin) on the left is from Berlin, Germany, and is made of wood, ivory, and metal. It was made in 1883. The

flöte (transverse, or side-blown, flute) on the right is from Austria. It was made of wood, ivory, and metal in the 1800s. This is an ancestor of the current flute - notice how different it looks!

The next three pictures show a variety of European brass instruments. In the 1800s, a new type of ensemble, the brass band, began its heyday. Thanks to new instruments and adjustments to current instruments that were invented during this time, as well as the population shifts to towns and cities due to the

Industrial Revolution, many cities and towns had their own brass bands. People enjoyed making music together, and it was a nice way to unwind after work! Some bands played competitively, and others just played for fun. The brass band activity lasted until the mid- to late-1900s, depending on the country. Check out all of the different brass instruments they had to work with during the time in history when brass bands were the hip thing to do.

This instrument is called an oktavin. It's a single-reed pipe from Saxony, which is now Germany. It was made near the year 1910. It's an interesting instrument - it's almost like someone put the mouthpiece and barrel of a clarinet into the boot of a bassoon and added a bell to it.

This instrument, the

sackbutt, is a predecessor of the trombone. This particular example is a replica instrument, made in the 1900s, but modeled after Renaissance (from approximately 1400-1600) era

sackbutts. The name roughly translates to "to pull out the end." (Makes sense when you think about how the instrument is played, right?)

These instruments should look somewhat familiar to the 4th and 5th graders out there. The top instrument is an

ottavino (piccolo) from the early 1900s. The middle instrument is a

flauto (flute) from 1872. Notice how different it looks from today's flute - it has far fewer keys, and the key mechanism is designed differently. The bottom instrument is from the brass family. It's a

bass tromba (valved trumpet) from 1880. Judging by its name (

bass tromba), do you think it's lower or higher than a normal trumpet?

Look at this large instrument! It's a

contrabasso ad ancia (contrabass reed pipe). Remember that the musical prefix "contra-" means below, so contrabass instruments are even lower than bass instruments. For examples of ginormous, rather impractical (and rarely seen) instruments, check out the following links to images:

contrabass flute,

contrabass clarinet, contrabassoon,

contrabass saxophone (it's the biggest one in the linked picture), and

contrabass trombone. Holy oh my goodness. Anyway, back to the Italian instrument below: It was made in 1925, and can be played with either a single or double reed.

Check out this cowbell! This

glocke (bell; connection - remember that the glockenspiel is also referred to as orchestra bells...glocke = bells) is from 1894. The display sign says that distinct cowbell pitches make it easier to locate specific cows. The French translation of the word is

cloche.

If the previous cowbell wasn't enough to cure your fever, feast your eyes on this monster! It's a

trychle (bell; translated as

toupin in French). The display sign states that "varied bell sizes and pitches create a wash of sound."

There are two Austrian

okarinas in this picture.

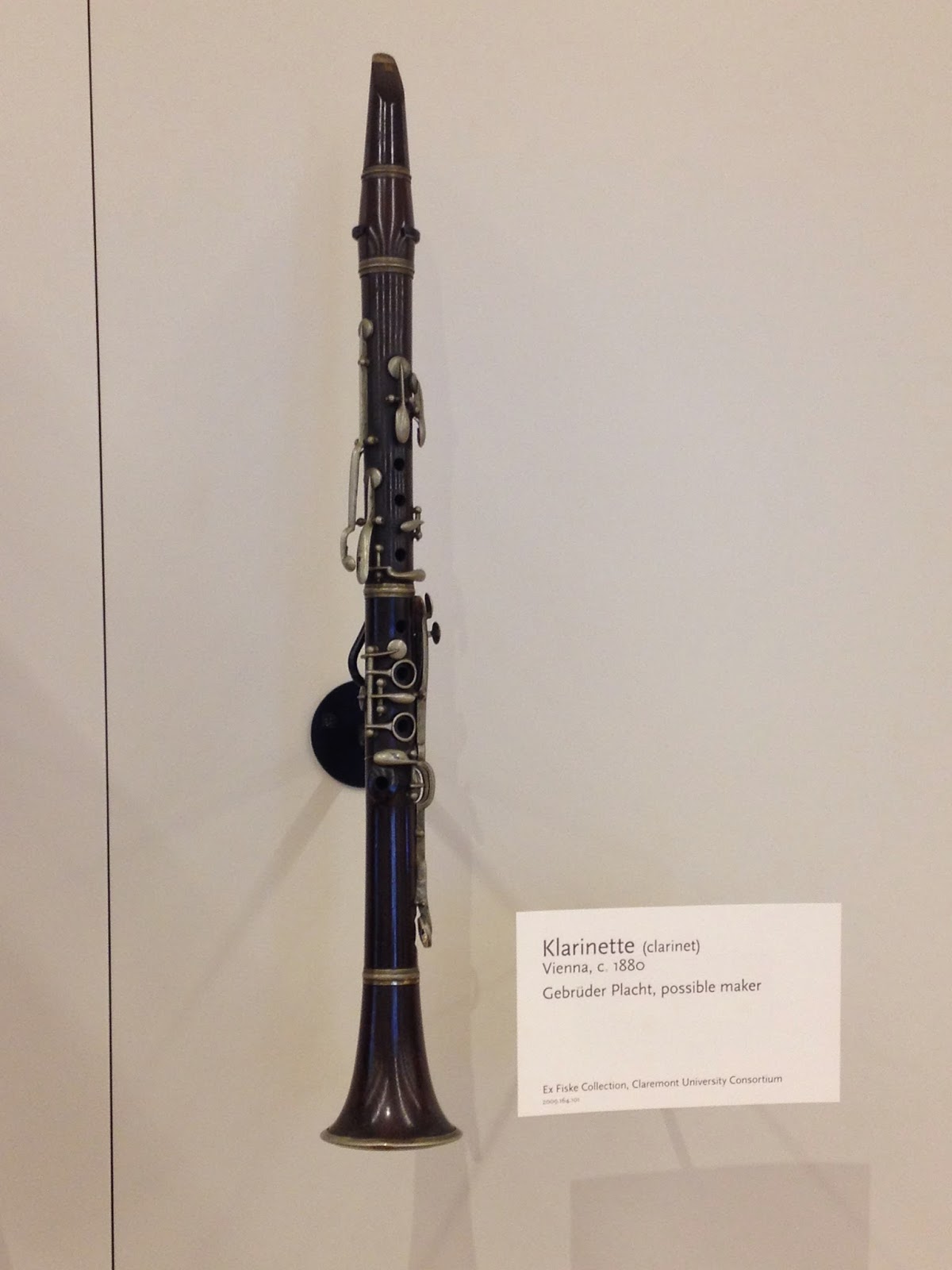

This

klarinette (clarinet) from 1880 is intriguing - the keywork is different than

modern day clarinets.

The same goes for this

flöte (transverse, or side-blown, flute) from 1827. Compare its keywork to that of the modern flute.

Compare the Austrian flute pictured above to this slightly earlier English flute. This was created around the year 1800. Compare this one to the

modern flute as well - it is definitely different!

Musical instrument inventor Adolphe Sax (1814-1894) grew up in Belgium and moved to France. He played flute and clarinet, and invented the saxophone (in addition to many other instruments, as well as modifications to existing instruments, like adding valves to brass instruments to increase the number of pitches they could play).

Speaking of valved brass instruments...here's a display that is grouped by category (brass trumpet) and not by country of origin. Check these out! The huge one at the bottom has the range of a tuba, but is constructed to look like a trumpet. Obviously it's not very practical (and I didn't know it existed until seeing it here!), but it looks neat.

Traveling across the Atlantic Ocean...the next two exhibits have to do with ethnic music that moved from Europe to North America (the United States, specifically).

The 4th graders learned about klezmer music this year before the winter concert! I'm sure if you asked one of them, they'd tell you that it's meant to use instruments to mimic the human voice (laughing, crying, talking, singing, etc.).

"With sounds that evoke ancient sacred chant, the lively soul of klezmer music (kley-zemer, Hebrew for "vessel of melody") is rooted in the gatherings, celebrations, and dances of Jewish Eastern European and Yiddish German communities.

"Poor wandering

klezmorim were resourceful musicians—using whatever instruments they could afford and borrowing musical ideas from Jews and non-Jews alike.

"This innovative spirit helped klezmer endure alongside new musical styles. Between 1880 and 1924, war and anti-Semitism drove more than three million Jews to North America. Always creative, immigrant

klezmorim embraced their new surroundings by experimenting with sounds from jazz and by replacing softer stringed instruments with louder brass and accordions in the recording studio. While continuing to add richness to Jewish American culture, klezmer has also enjoyed popularity among non-Jews."

The painting on the left is of a Jewish wedding being led by

klezmorim. The caption for the picture on the right reads, "Jewish music was big business for publishers in New York City."

The instrument on the left is a cornet (similar to a trumpet, but its bore is conical (shaped like a cone), not cylindrical) from 1890. The instrument on the right is a clarinet. The display sign reads, "Forced to travel light, many immigrant

klezmorim bought American-made instruments after arrival in the United States."

The trombone can also be used in klezmer music. The manufacturers of this one were particularly influential: "The Alexander Brothers' shop has influenced brass instrument manufacturing since the 1860s."

This violin is from the

Czech Republic, from around the year 1910. "Violins and other string instruments have been in use in klezmer music since the 17th century."

This is a bass helicon in F, made in

Boston, Massachusetts, in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Note its similarity to a

sousaphone. "Brass instruments were integrated into klezmer music in the late 19th century."

"Polka (Czech for 'little step') is best known as lively Bohemian dance music with a distinctive oompah beat, but American polka blends diverse regional traditions and popular styles.

"Nineteenth-century Czech, Polish, Slovenian, and German working-class immigrants brought European social dances to urban and rural communities. Around 1900, polka music was played by bands that featured clarinets, brass, and fiddles. By 1940, the accordion had taken center stage.

"In the 1950s, Li'l Wally Jagiello, the 'Polka King,' exemplified polka's rise in the recording industry, radio, and television, moving polka from dance halls to American homes. Polka styles have continued to change, melding with such diverse genres and styles as jazz, Latin, punk, and Tohono O'odham

waila (from the Spanish

baile, or dance)."

"Peacock Pearl" drumset - Check out the landscape on the head of the bass drum!

Below the trombone from left to right are a King baritone (King is the brand), another baritone (related to the euphonium the way the trumpet is related to the cornet - baritone has a cylindrical bore, whereas the euphonium has a conical bore so it sounds a bit warmer and sweeter because of the way the air moves through the instrument), a tuba pitched in F, an accordion hanging on the wall, a space-saving variation on the string bass next to that, and an electrochord (stand-up accordion) is the odd silver thing on the floor up front.

"First invented in the 1820s, the accordion had volume and portability that were ideal for polka bands."

This baritone was made in

Elkhorn, Wisconsin, in 1931. "Bass brass instruments are used in polka music to provide strong downbeats."

The clarinet on the left was made in

Elkhart, Indiana, in 1925. Metal clarinets like the one on the right are not made anymore. Like jazz saxophonists, polka saxophonists often switch between saxophone and clarinet.

North America

"A new type of band—the concert band—developed in the United States in the mid-to-late 19th century.

"These popular community bands were derived from military bands, but were larger and included a wider variety of instruments than the traditional brass used in military contexts. One of the most popular America bands of the early 20th century was the one led by

John Philip Sousa. Although best known for playing marches, ironically, they never played while marching. Sousa's band also performed opera excerpts, orchestral pieces, popular songs, and light classics. In a time of limited access to recordings and symphony orchestras, the Sousa band became a live concert sensation, touring both the United States and the world many times."

The photograph on the right side of the display sign is of the U.S. Marine Band in 1891.

"Band, ten-hut!" With this call, high school and college musicians across the country snap to attention, ready to perform.

"Marching band traditions in the United States are rooted in the military. The fife and drum regiments of the American Revolution (1775-1783) inspired both school marching bands and the drum and bugle corps of today. With the rising popularity of collegiate football in the late nineteenth century, some wind bands took to the playing field wearing military-inspired uniforms. Many percussion and low-brass instruments were too bulky to play while marching. As a remedy, instruments invented solely for marching ensembles, such as multi-toms and sousaphones, were designed to rest on the player's shoulders.

"Today, audiences enjoy marching styles ranging from militaristic block formations to fast-paced shows filled with pageantry."

Upper left photo on the display: "The 'Block P' of Purdue University, West Lafeyette, Indiana, was the first-ever show-style block formation, 1907."

Lower left: "The first occurrence of 'Script Ohio' by the Ohio State University Marching Band, 1936." Fun fact: The "i" is traditionally dotted by a senior sousaphone player.

Right: "'Contras' or contrabasses are marching versions of tubas; Bluecoats of Canton, Ohio, 2011."

Top instrument: Dynasty II soprano bugle from Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, from around 1980. It's made of brass and chrome. "As drum corps bugles evolved from being valveless to having one or two valves, the Dynasty lines became the leading models."

Second instrument from top: Bugle from London, England, from 1957-1958.

Third instrument from top: T101 "Titleist" bugle, made by Getzen. "Early corps competitions maintained valveless bugle traditions. Horizontal valves were illegal in these contests because they could be hidden by the player's hand."

Bottom instrument: Dynasty II baritone bugle. "Two-valved instruments were originally not permitted in competition; baritones were allowed in 1978."

"Modern-day marching and community bands have their roots in 19th-century American military bands.

"The instruments used in these early bands had to meet one major criterion: portability. The demand was for instruments that could easily be carried from camps to battlefields.

"Beyond that, the instruments evolved to suit the unique situation of a band marching at the front of a column of troops. Over-the-shoulder horns were specifically designed to project the instrument's sound behind the play, the better to be heard by the soldiers marching at the back of the band."

The two instruments on the left are over-the-shoulder soprano horns, and to the right (underneath the television screen) is a pair of over-the-shoulder alto horns.

A variety of over-the-shoulder horns, including two tenors on the left and a bass on the right.

Piano players, listen up - this next exhibit is for you. Have you heard of a little brand called

Steinway? It's based out of Astoria, which is a neighborhood in New York City (see the map below).

In the gift shop, I bought a documentary called

Note by Note: The Making of Steinway L1037. It follows the making of a single concert grand piano, which takes 12 months to make by hand. It is amazingly detailed work, and it was a very interesting documentary. If people are interested, maybe we'll have a viewing party during a couple recesses at school. (Interested parties may include pianists, musicians, people who like to know how things work, people who like to see how things are made, people who like working with their hands, woodworkers, etc.)

Here's some of the information that's in the Steinway display at the MIM.

"At the time of its introduction in the 1930s, Steinway's Accelerated Action was considered one of the greatest advances in piano making.

"By placing the keys on a support and adjusting the lead weights, Steinway made its piano keys respond even more quickly to the touch with far less strain and effort. Keys leap back when played as though they are on springs. This kind of sensitivity makes the most difficult passages playable with incredible lightness and precision. Once all parts are assembled, Steinway subjects its keyboards to the 'Pounder,' a robot with 88 fingers that strikes each key 10,000 times in less than an hour. Following this rigorous test, voicing of the instrument takes place, a process in which only the most skilled technicians fine-tune the piano's sounds."

Picture on the left: "Overstringing in process"

Picture in middle: "Two recently strung pianos in final testing"

Picture on right: "Patent drawing"

"Made from spruce and built to withstand enormous force, Steinway's elegant soundboard serves two purposes: to support the strings and to project sound.

"The Diaphragmatic Soundboard, patented in August 1936 and February 1937, was an important breakthrough in soundboard construction. Expertly tapered to be thinner at its edges, the Diaphragmatic Soundboard created a richer, more resonant tone and a longer duration of sound. Owing to its domed construction, the soundboard is able to transmit the vibrations effectively, evenly distributing sound and tone.

"This important innovation allowed the string vibrations more room to roam, resulting in a powerful and brilliant sound."

Picture on left: "A craftsman in the final stage of making the soundboard"

Picture on right: "Patent drawing"

"In December 1859, Henry Steinway Jr. introduced his latest accomplishment: overstringing.

"An innovation in string placement, overstringing means that longer bass strings cross over shorter mid-range and treble strings, making it possible for bass strings to be placed closer to the soundboard's more resonant center. The result translated into balanced sound, producing bass notes that are as deep and full as high-pitched treble notes are crisp and bright.

"Overstringing presented a challenge, however. The longer bass strings significantly increased string tension, and Steinway developed yet another innovation to offset the enormous pressure brought to bear on the piano's frame. A 340-pound cast-iron plate has the mighty task of supporting nearly 40,000 pounds of string tension. Together, the cast-iron plate and overstringing designs established a standard used in all modern pianos."

Check out the layers of a grand piano, including the cast-iron plate in the aforementioned description of overstringing.

"Wrestling wood into the shape of a piano rim is no small task.

"Wrestling wood into the shape of a piano rim is no small task.

"In 1880, C. F. Theodore Steinway simplified the process by introducing a rim-bending press that could shape inner and outer rims simultaneously, resulting in the grand piano's unmistakable elegant curves. The 'wood-bending machine' contours the wood as the glue bonds nine continuous strips of maple overnight. After the clamps are removed, the case is upended and left for a month or more to fully cure in a controlled environment. Only then is the rim ready to serve its function by containing the strings' vibrations and transferring them to the soundboard."

Picture on left: Factory worker finishing rim

Picture in middle: Rim-bending machine, 2008

Picture on right: Patent drawing

"Since the company's formation in 1853, generations of Steinway craftspeople have upheld founder Henry E. Steinway's commitment to continually improve the instrument.

"Steinway & Sons' quality designs and technical innovations have set a precedent for the look and sound of today's concert grand. This dedication to perfection has made Steinway pianos the standard by which all others are measured.

"Like Steinway pianos,

Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture resulted in unparalleled designs and innovations. A lifelong musician, he adored Steinway pianos and incorporated spaces for musical performance into many of his buildings, including nearby Taliesin West."

Picture on the left: "Voicing" the hammers

Picture in the middle: Patent drawing

Picture on the right: "Frank Lloyd Wright improvises on a Steinway, 'letting the piano play itself,' as he often put it. Guggenheim Museum, 1953."

Moving away from pianos and towards handbells...

"English-style handbells have become increasingly popular in the United States since the mid-nineteenth century.

"While handheld bells date to ancient times, modern English handbells first appeared in the 1600s. Initially, these tuned bronze instruments helped musicians practice for playing large church tower bells, but soon groups across England were ringing handbells as musical entertainment.

"The handbell phenomenon crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the 1800s, with various performing groups quickly gaining popularity. American ringers obtained their instruments from England until the early 1960s, when Schulmerich Carillons Inc. began producing American-made handbells designed by Jacob Malta, who went on to found Malmark Bellcraftsmen in 1973. Today, handbells are commonly rung in churches and schools. Professional and amateur ensembles and soloists also perform across the country."

Notice the large variation in sizes between the handbells in the photo below. Those things that look like buckets are really, really low handbells.

This big baby is made of aluminum, lamb's wool, and plastic. "Developed and patented in the early 1990s, aluminum bells are about 1/2 the weight of bronze bells. The G1 is the world's lowest-pitched handbell in production."

"An American invention, the drum set offers an ever-expanding range of musical possibilities.

"Until the late 1800s, ensembles containing cymbals and snare and bass drums required at least three percussionists. The advent of mechanical foot pedals, along with cymbal suspension, allowed a single musician to play multiple percussion instruments at once.

"In novelty acts and in theater and circus bands, pedals and suspended cymbals were used alongside many other experimental sound-effect contraptions. Early twentieth-century jazz musicians adopted the drum set and assorted 'traps,' including cowbell, woodblock, tom-tom, and wire brushes (originally patented as flyswatters). The perfection of the hi-hat—two cymbals played with a foot pedal—in the 1930s completed the standard drum set as heard today in numerous music genres throughout the world."

Hey, 4th and 5th graders, do you remember when we talked about the drum set? Look at how extensive this one is! (And check out the photo on the display sign above this one!)

From there, we moved on to the jazz exhibit.

This 1191PV "Victory" drum set (made in 1944) is interesting. "Uncommon wooden rims and lugs are due to World War II manufacturing restrictions on metal use."

The baritone sax (also known as the bari, pronounced like "berry") is on the left, and the string bass is on the right. The double bass (sometimes called the upright bass to distinguish it from the electric bass in jazz band) has been a part of jazz since the genre's origins in ragtime.

This fancy instrument is a Martin Committee trumpet.

"Since bursting on the music scene in the early 1900s, jazz has inspired generations of musicians and fans.

"A blend of Creole, African, European, and Native American influences,

New Orleans was a hotbed of musical innovation at the turn of the twentieth century. Musicians fused ragtime and African rhythms in this Louisiana city—the acknowledged birthplace of jazz. Bending notes in new ways, players used instruments to mimic the human voice.

"Jazz spread up the Mississippi River to Chicago, Kansas City, and New York in the 1920s. The music also made its way across the Atlantic to Paris, France. During this 'Jazz Age,' charismatic artists such as

Louis Armstrong helped popularize the form. Other jazz greats, including

Duke Ellington and

Count Basie, got their start at this time."

Picture on the left: The Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, New York City, circa 1924

Picture on the right: Louis Armstrong at Carnegie Hall, New York City, 1947

"Women have made jazz music since the genre's beginning.

"Women vocalists—and to an extent, pianists—were support in the jazz industry for much of the twentieth century, but most instrumentalists faced resistance in this male-dominated environment. During World War II, all-female bands booked an increased number of gigs until male soldiers returned to the United States.

"With remarkable abilities as performers, composers, and arrangers, women such as Mary Lou Williams and Melba Liston found a degree of acceptance in the wider jazz community. Beginning in the 1960s, the women's liberation movement cultivated a new public appreciation of the significant contributions of female jazz artists. Festivals celebrating women in jazz first appeared in the late 1970s and now occur around the world. Today, women remain some of jazz's finest artists."

Picture on the left: International Sweethearts of Rhythm saxophone section, 1940s

Picture on the right: Grammy-winning bassist, vocalist, and composer Esperanza Spalding, 2012 (4th and 5th graders, you've seen her play)

And finally, before my friends and I left, we checked out the Experience Gallery. I should have stood next to this gong so you could see how tall it really is. If you can picture it...I'm 5'10" and the top of my head came up to about the frame right above the gong. The whole frame was at least a couple feet taller than me. By the way, we all tried it, and it's got a very resounding whoosh to it.

I hope you enjoyed my vacation! I'll have to go back sometime and get some pictures from South America...